Swimmer ready to make history

Call him crazy.

Or completely crazy.

Or the most interesting swimmer in the world.

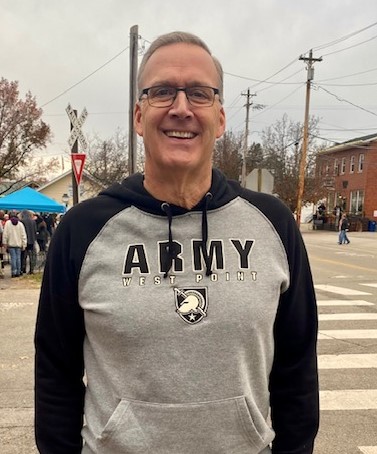

All apply to Maumee native John Muenzer, a grandfather of 11 who completes superhuman swims — his next (and final) one is an overnight 20-miler off the shark-inhabited California coast — on an everyman diet.

Yep, there’s hope for all of us! Muenzer keeps the doctor away with two trips to McDonald’s a day, including his Breakfast of Champions: a bacon, egg, and cheese McMuffin and a large Coke. For lunch, it’s a cheeseburger Happy Meal with extra fries in lieu of the apple slices.

“I was the generation before GNC,” he said with a laugh.

But, while you can call Muenzer a lot of things, there’s one thing you can’t: a quitter.

Sticking to the theme of night swims in California, the man is more determined than a prisoner trying to escape Alcatraz, which, by comparison, required only a leisurely 1.25-mile dip in the bay.

Muenzer, a St. John’s Jesuit and University of Toledo graduate, set out to accomplish the Triple Crown of Open Water Swimming: a saltwater gauntlet that includes crossing the English Channel (21 miles), a spin around Manhattan Island (28.5 miles), and an odyssey from Catalina Island to Los Angeles (20.5 miles).

Now, at age 60, nearly four decades after he first made international waves with an aquatic ultra-marathon from Canada to Cedar Point (he swam 36 miles in just over 24 hours) and 13 years after he spanned the English Channel (13 hours, 12 minutes), he’s ready to finish the job.

Muenzer will leave Catalina Island at 11 p.m. on Aug. 2.

If and when he reaches the mainland, he’ll join a club some 20 times more exclusive than the number of Everest alums (267 men and women have completed the Triple Crown). He’ll also be-come the oldest person to polish off the Grand Slam of marathon swimming, a feat that includes the Big Three conquests and a 24-miler in Tampa Bay.

“When I started trying to do these swims, it was 100 percent to see if I could do them,” said Muenzer, a salesman by day who resides in Loveland, Ohio, outside Cincinnati. “Then it morphed into setting an example for my grandchildren. Set your goals and never give up. ... I’ve been working on this most of my life. I’m pretty excited to be in the position physically to do it, with my shoulders and everything hanging together. It really is amazing.”

Of course, he’s the first to admit: It’s also a little, well, bananas.

His upcoming swim, he said, will “probably be the most dangerous” of his Grand Slam journey.

Which is saying a lot.

Some readers might know a little about Muenzer’s backstory, including his swim across Lake Erie in 1983.

That followed his Hall of Fame career at Toledo and whet his palate to take on the granddaddy of open-water crossings: the arm of the Atlantic between England and France we know as the English Channel.

Life intervened. Work, marriage, seven children.

But, in 2009, he jumped back in, shed 35 pounds from his 6-foot-5, 260-pound frame during a year of training, and put the check on his bucket list. Then, after his family was rocked by tragedy in 2016 — his beloved son, Dan, was killed in a motorcycle accident at age 23 — he found a small measure of peace in returning to the deep. He knocked out the Manhattan Island swim in 2018.

Muenzer has been to hell and back in the high waters.

Consider: On his swim across the Channel, Muenzer got caught in the wake left by a way-too-close cargo ship, rammed by a dolphin, and stung by 18 jellyfish, the last encounter of which was as delightful as it sounds. “I tell people what it feels like,” he said. “Take a nail and a hammer and put a nail into your arm. Then take your hot iron and put it right on top of the nail.”

And yet the nails and hot irons? They were the pleasant part of the swim.

Similar to the conditions he’ll face in August, there was also also the small matter of navigating 20-plus miles in 61-degree waters — way colder than it sounds — wearing only trunks, a swim cap, and goggles.

It’s inconceivable, really.

For perspective, one mile of swimming is considered the equivalent of four miles of running (or more, judging by the math used in the famed Ironman Triathlon, which features a 26.2-mile marathon, a 112-mile bike ride, and a 2.4-mile swim).

In practice alone — Muenzer wakes up at 4:45 a.m. six days per week — he sneaks in what amounts to running a three-hour marathon before work. (That McDonald’s diet always gets you with fine print!)

But the human body can be a funny thing.

And few men have a greater spirit than Muenzer.

He took me through what he expects from his milestone August swim, beginning with setting off in the dead of night.

“I’ll be really, really nervous standing there,” he said. “You go through this fear of the unknown. You’re entering the wild. You’re entering a new world, and I have no control over it, and I’m insignificant as hell. An orca, a great white, a lemon shark, jellyfish, they don’t give a crap who I am. This is their world, and I’m entering it.”

From there, he’ll turn into something of a maritime machine, waging a battle against mind and body, one stroke after another, hour after hour.

There will be times he wants to tell the crew on the boat by his side he’s done. There will be times his bones will feel like ice, and it’s as if his arms are encased in concrete and his legs on fire, and his stomach is hosting the Royal Rumble.

(By the way, his sustenance will include chunks of chocolate, a bag of Lays potato chips, peanut butter and jelly squares, and three cans of Coke, along with plenty of warm tea and water.)

But ...

Then he’ll think of his family — including his late son and saintly wife, Mary — and all that he has sacrificed in pursuit of his damn-near-impossible goal, and, somehow, he’ll carry on.

“You have to get a second, third, fourth wind,” Muenzer said. “I’ll walk through it mentally. At that point, I will have swam 1.4 million yards (795 miles) to get ready. If you quit with four hours to go, here’s what you’re facing. You’ve got to go back to the hotel, answer everybody’s questions, fly all the way home, train another year, fly all the way back.

“I start to think about all the hours that it will take for me to get back to the exact point I’m at right then where my mind is telling me [to stop], or you can finish the final four hours. That’s the process you go through multiple times, and you keep going.”

If all goes to plan, the rest will be swimming history.

Contact David Briggs at dbriggs@theblade.com or on Twitter @DBriggsBlade.